Controversial Nutrition Topics: Top Nutrition Controversies for Nursing Students

Nutrition science occupies a unique position in healthcare, where evolving evidence, patient values, and public messaging often intersect in ways that generate ongoing controversy. For nursing students, this can make learning and applying nutrition principles particularly challenging. Recommendations that once appeared settled may be questioned as new research emerges, while popular media and the food industry frequently amplify selective findings, adding further complexity to clinical decision-making. As a result, many nutrition topics remain actively debated within both academic and clinical settings.

These debates—commonly described as nutrition controversies—are not merely theoretical. They influence patient counseling, chronic disease prevention strategies, and interdisciplinary communication among healthcare teams. Nurses are often at the frontline of these discussions, translating evidence into practical guidance for individuals with diverse health needs, cultural backgrounds, and personal beliefs. Developing the ability to critically evaluate evidence, recognize uncertainty, and communicate balanced information is therefore an essential nursing competency.

This article examines controversial nutrition topics that are especially relevant to nursing education and practice. Rather than promoting a single dietary philosophy, it emphasizes evidence appraisal, clinical context, and patient-centered care. By exploring areas where scientific findings are complex or contested, nursing students can better understand why disagreements exist, how professional guidance is formed, and how to support informed decision-making in real-world healthcare environments. Ultimately, engaging thoughtfully with nutrition controversies strengthens clinical judgment and prepares future nurses to navigate nutrition-related questions with clarity, confidence, and professional integrity.

150 Controversial Nutrition Topics

I. Dietary Fats and Heart Health (50 topics)

- Is saturated fat the main cause of cardiovascular disease?

- Are trans fats more harmful than saturated fats?

- Does coconut oil increase risk of heart disease?

- Are monounsaturated fats truly cardioprotective?

- Should total fat intake be limited for obesity prevention?

- Are plant oils better than animal fats for cardiovascular health?

- Does butter consumption affect LDL-cholesterol?

- Are dairy fats neutral or protective for heart health?

- Does replacing fat with refined carbs improve heart health?

- Are omega-3 supplements effective for cardioprotective effects?

- Should cholesterol intake guidelines be stricter?

- Are polyunsaturated fats always beneficial?

- Can fat restriction hinder metabolic health?

- Are low-fat diets sustainable for long-term weight control?

- Is the omega-6 to omega-3 ratio important in disease prevention?

- Does grass-fed meat reduce cardiovascular risk factors?

- Are processed meats worse than unprocessed meats for heart disease?

- Is the Mediterranean diet the ideal nutrition approach for cardiac patients?

- Should dietary fat guidelines differ by age and gender?

- Can replacing animal fat with plant-based fats improve health outcomes?

- Do saturated fats influence insulin response?

- Are heart health outcomes dependent on total diet quality rather than fat alone?

- Does margarine increase risk factors more than butter?

- Are nut-based diets superior for cardiovascular health?

- Can ketogenic diets improve metabolic risk factors without harming heart health?

- Are certain saturated fat sources cardioprotective?

- Do fatty acids impact blood pressure?

- Can eggs be part of a heart-healthy diet?

- Are dietary fats linked to cognitive decline?

- Should fat reduction remain a primary public health goal?

- Does dairy cheese affect cardiovascular health?

- Are palm oil and tropical oils harmful?

- Can dietary fats affect inflammation markers?

- Should total caloric intake be prioritized over fat type?

- Are vegan diets low in fat safer for heart health?

- Does nut consumption influence obesity prevention?

- Are fried foods more harmful than fat content alone indicates?

- Does olive oil supplementation reduce risk factors?

- Are butter substitutes necessary for healthy eating?

- Does high-fat dairy have protective benefits for adults?

- Should saturated fat limits be universal or individualized?

- Do health professionals overemphasize saturated fat?

- Is there a link between fat intake and type 2 diabetes?

- Are cardioprotective fatty acids sufficient in Western diets?

- Should fat consumption guidelines differ by ethnicity?

- Are plant-based meat fats better than animal fats?

- Do high-fat diets affect glycemic control?

- Can moderate fat intake coexist with low sugar intake for heart health?

- Is the “low-fat” trend still valid in modern nutrition?

- Do processed plant fats carry hidden health risks?

II. Sugars, Sweeteners, and Diabetes (50 topics)

- Are artificial sweeteners safe for metabolic health?

- Do artificial sweeteners impact type 2 diabetes risk?

- Can sugar substitutes affect insulin response?

- Is high-fructose corn syrup worse than table sugar?

- Do soft drinks drive obesity?

- Is natural sugar healthier than refined sugar?

- Are sugar alcohols safe for long-term use?

- Can sweeteners impact gut microbiota?

- Should children avoid artificial sweeteners entirely?

- Do diet sodas improve glycemic control?

- Can stevia influence blood glucose levels?

- Is there a difference between “sugar-free” and “no added sugar”?

- Does sugar intake increase risk of heart disease?

- Are low-calorie sweeteners associated with weight gain?

- Should diabetics prefer sweeteners over sugar?

- Are sugar substitutes linked to cravings for sweet foods?

- Can artificial sweeteners contribute to metabolic syndrome?

- Do natural sweeteners like honey or maple syrup affect blood glucose?

- Are sugar alternatives safe for children’s health?

- Does replacing sugar with artificial sweeteners reduce obesity risk?

- Can sweeteners affect satiety signals?

- Do sugar-sweetened beverages increase type 2 diabetes incidence?

- Should sugar guidelines be universal?

- Are sugar-sweetened foods worse than liquid sugar?

- Does hidden sugar in processed foods influence risk factors?

- Can sweeteners improve compliance in nutrition therapy?

- Is excessive sugar intake linked to fatty liver disease?

- Do sweeteners have long-term health consequences?

- Are sugar substitutes metabolically neutral?

- Does sugar influence cardiovascular biomarkers?

- Should sweeteners be restricted during pregnancy?

- Can sweeteners reduce total caloric intake effectively?

- Are sugar-sweetened breakfast foods harmful for overall health?

- Do sugar-free products mislead consumers about healthy eating?

- Can dietitians safely recommend artificial sweeteners for weight management?

- Is sugar addiction a valid concept in public health?

- Do sugar substitutes affect children’s appetite regulation?

- Are sweetened foods more addictive than high-fat foods?

- Should sweeteners be considered in nutrition studies on obesity?

- Does sugar consumption influence body weight independently of calories?

- Are artificial sweeteners beneficial for cardiometabolic health?

- Do low-glycemic sweeteners improve blood glucose control?

- Are there gender differences in sweetener effects?

- Can artificial sweeteners replace sugar safely in school programs?

- Should public health campaigns target sweetener awareness?

- Are sugar substitutes linked to cardiovascular events?

- Can sweeteners reduce disease risk?

- Do sweeteners impact satiety differently than sugar?

- Are sugar and sweeteners overemphasized compared to total diet quality?

- Can moderation in sweetener use support long-term health?

III. Plant-Based Nutrition and Meat Alternatives (50 topics)

- Are plant-based diets sufficient for nutrient needs?

- Can plant-based diets prevent obesity?

- Do plant-based diets reduce cardiovascular risk factors?

- Are plant-based diets effective for type 2 diabetes management?

- Do plant-based diets cause nutrient deficiencies?

- Should B12 supplementation be mandatory for plant-based diets?

- Can plant-based diets reduce metabolic risk factors?

- Are soy products safe for women’s health?

- Do plant-based meats replicate whole food nutrition?

- Are plant-based meats processed food concerns?

- Can plant-based meats influence body weight?

- Are omega-3 levels sufficient in plant-based diets?

- Can legumes replace meat for cardioprotective effects?

- Are plant-based diets sustainable long-term?

- Do plant-based diets reduce inflammation?

- Can plant-based nutrition improve glycemic control?

- Are plant-based diets suitable for athletes?

- Should plant-based meats be fortified for micronutrients?

- Can a whole food plant-based diet prevent type 2 diabetes?

- Are plant-based diets compatible with health at every size principles?

- Does plant-based nutrition improve cholesterol levels?

- Can plant-based diets support heart health in older adults?

- Do plant-based diets affect reproductive health?

- Can plant-based eating reduce risk of heart disease?

- Are soy protein sources equivalent to animal protein?

- Do plant-based diets influence metabolic syndrome markers?

- Are plant-based diets practical in low-resource settings?

- Can plant-based diets prevent obesity in children?

- Does plant-based nutrition support healthy eating habits?

- Are fortified plant-based meats reliable nutrient sources?

- Can plant-based diets reduce inflammation markers?

- Are plant-based proteins sufficient for muscle maintenance?

- Do plant-based diets affect cardiovascular health differently in men and women?

- Can plant-based diets improve insulin sensitivity?

- Should plant-based diets be recommended for women’s health?

- Are plant-based diets suitable for seniors at risk of sarcopenia?

- Can plant-based diets improve overall health outcomes?

- Are plant-based diets associated with lower disease risk?

- Do plant-based meats affect long-term body weight control?

- Can plant-based diets reduce risk factors for chronic disease?

- Are plant-based diets nutritionally complete without eggs or dairy?

- Should plant-based diets include fortified foods or supplements?

- Can plant-based diets improve metabolic biomarkers in diabetics?

- Are whole-food plant-based diets superior to processed alternatives?

- Can plant-based diets reduce LDL-cholesterol effectively?

- Do plant-based diets support health-promoting eating patterns?

- Are plant-based diets suitable for long-term adherence?

- Can plant-based nutrition improve cardiovascular outcomes?

- Are plant-based diets effective for weight management?

- Should plant-based nutrition focus on minimally processed foods for health benefits?

Is saturated fat the main dietary fat concern for cardiovascular health?

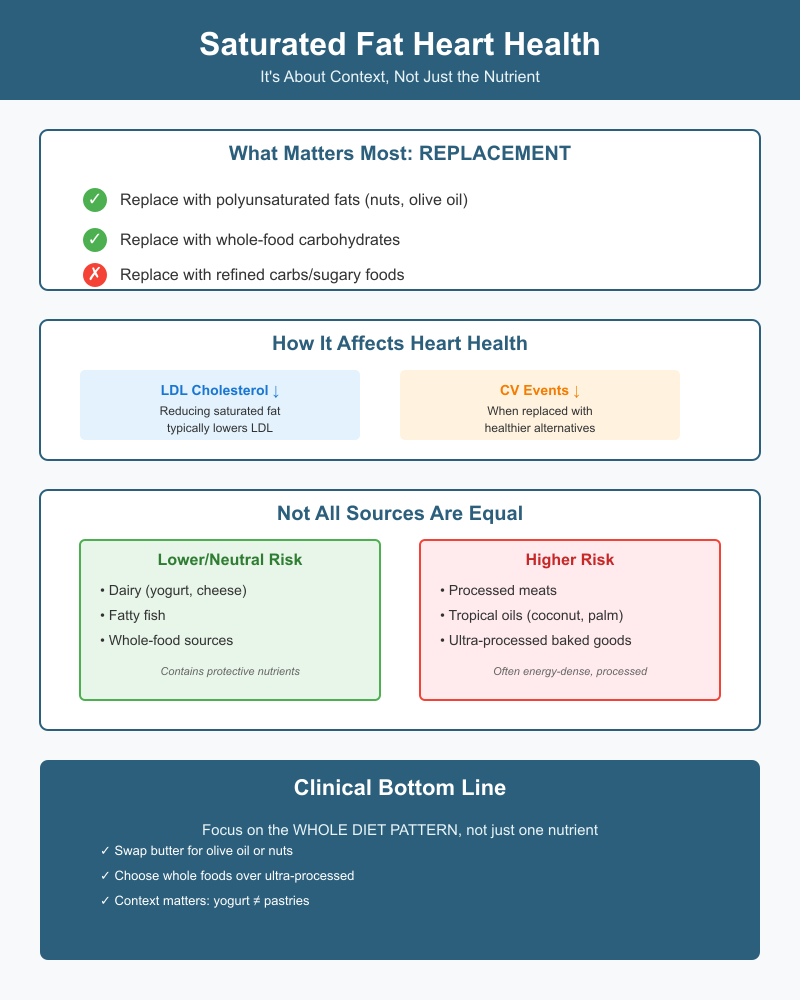

Saturated fat is often the headline nutrient when clinicians and the public discuss heart disease, but the full picture is more nuanced than a single “bad” nutrient. Current global guidance—built from randomized trials, cohort studies, and systematic reviews—frames the issue around what replaces saturated fat in the diet, the food sources that supply it, and how changes in intake affect established markers such as LDL-cholesterol and longer-term cardiovascular events.

How does saturated fat influence heart disease and cardiovascular risk factors?

At a mechanistic and population level, replacing the targeted nutrient with different replacement macronutrients matters:

- Cholesterol and lipids. Reducing intake of this class of fatty acids typically lowers LDL-cholesterol, a well-established causal factor for atherosclerotic disease. Changes in LDL explain much of the relationship between lowering the nutrient and reduced cardiovascular events in trials.

- Clinical outcomes. Umbrella reviews and meta-analyses of intervention and prospective studies generally find that lowering intake and replacing it with polyunsaturated fats or whole-food carbohydrate sources is associated with fewer cardiovascular events, though effects on overall mortality are smaller and study results vary by follow-up length and study design. This is why many authorities focus on replacement quality rather than absolute elimination.

Practical example for nurses: swapping butter on toast for olive oil or a small portion of mixed nuts tends to lower LDL and aligns with dietary patterns shown to reduce event risk, while simply replacing saturated fat with refined carbohydrates (sugary foods) may not improve heart disease outcomes.

Are some saturated fat sources more cardioprotective or risky than others?

Evidence increasingly points to food-level effects rather than only nutrient-level effects. Foods that happen to contain similar amounts of saturated fatty acids do not carry identical risks:

- Dairy vs. processed meat. Several cohort analyses and reviews report that dairy sources (cheese, yogurt) are not associated with higher cardiovascular risk and may even show neutral or modestly protective associations, whereas processed red meats are more consistently associated with higher risk.

- Tropical oils and ultra-processed products. Coconut and palm oils, and industrial products high in saturated fat (many baked goods, pastries), may unfavorably affect lipids and are often energy-dense and highly processed—traits linked to worse cardiometabolic outcomes. Conversely, whole foods with mixed fatty acid profiles (e.g., fatty fish, some dairy) can carry additional nutrients or bioactive compounds that mitigate risk.

Clinical vignette: A patient who eats full-fat yogurt and modest amounts of cheese as part of a Mediterranean–style pattern may have very different cardiovascular risk implications than someone who consumes large amounts of processed pastries and fried foods, even if absolute saturated-fat grams look similar on a diet log.

What do health professionals and registered dietitian guidelines say about saturated fat intake?

Major public-health bodies and professional organizations converge on a pragmatic message: limit saturated fat as a share of calories and prioritize healthier replacements. Guidance examples include:

- The World Health Organization recommends keeping saturated fatty acids to ≤10% of total energy and shifting the balance toward unsaturated fats.

- Professional cardiovascular and nutrition organizations advise reducing intake and replacing those calories with polyunsaturated fats, oily fish, or unrefined plant foods rather than refined carbohydrates. This is the basis for many national dietary guidelines (e.g., Dietary Guidelines for Americans).

From a practice standpoint, multidisciplinary teams—clinicians, nurses, and the credentialed dietitian—should emphasize individualized counseling: assess overall eating patterns, comorbidities (for example, marked dyslipidemia), cultural foodways, and feasibility. For many patients, promoting patterns such as the Mediterranean diet (rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats) or emphasizing plant oils and whole foods produces measurable lipid improvements and better long-term outcomes than focusing narrowly on gram targets.

Are artificial sweeteners safe for metabolic health and diabetes management?

Artificial sweeteners are compounds used to provide sweetness with minimal or no calories. They are found in many sweetener products marketed to reduce energy intake in foods and beverages. Common examples include aspartame, sucralose, and stevia-based sweeteners. Their widespread use stems from the intent to help manage body weight and reduce the intake of sugar, but questions remain about their impact on metabolic regulation and clinical outcomes.

Do artificial sweeteners affect blood glucose, type 2 diabetes risk, or insulin response?

Research examining whether artificial sweeteners affect blood glucose levels or insulin response has produced mixed results. Some short-term metabolic studies show little to no effect on acute post-prandial glucose or insulin when sweeteners replace sugar in foods. The underlying mechanism appears to be that these non-nutritive compounds do not contribute calories or directly raise blood glucose.

However, there is evidence that habitual consumption may influence glucose regulation indirectly. Some observational studies suggest associations between frequent intake of artificially sweetened products and higher incidence of type 2 diabetes. It remains unclear whether this reflects a causal relationship or whether individuals predisposed to glucose intolerance are more likely to choose low-calorie options. The complexity of human dietary patterns and lifestyle confounders makes it difficult to establish a direct causal link from observational data alone.

What are the long-term health consequences and controversies around artificial sweeteners?

Long-term health outcomes related to artificial sweetener use continue to be debated. Supporters point out that replacing caloric sugars with non-nutritive sweeteners may reduce overall energy intake, which could be beneficial for weight management and associated chronic conditions. In contrast, critics raise concerns about compensatory eating behaviors, where individuals consuming artificial sweeteners might consume additional calories elsewhere, potentially negating benefits.

Beyond energy balance, there is active scientific discussion about effects on gut microbiota and appetite regulation. Some controlled trials in humans have reported subtle changes in gut microbial composition following certain artificial sweetener exposures, but the clinical significance of these shifts for cardiovascular health or glucose metabolism remains unclear and requires further high-quality research.

How should nursing students counsel patients about sweetener choice and food intake?

When advising individuals about sweetener selection, the approach should be evidence-informed and tailored to the person’s overall dietary habits and health goals. It is important to emphasize that replacing sugar with artificial sweeteners may be one tool to reduce added sugar intake, especially for those struggling with excess caloric consumption. However, the focus should remain on whole, nutrient-dense foods and beverages as the foundation of a health-promoting dietary pattern.

For example, recommending water, unsweetened tea, or beverages flavored with natural extracts can support hydration and reduce reliance on both sugar and artificial sweeteners. Where low-calorie sweeteners are used, guidance should be unambiguous that they are a substitute, not an addition, to a balanced diet. Encouraging mindful eating and awareness of portion sizes reinforces the connection between dietary choices and diabetes prevention or management.

It is also useful to discuss practical strategies, such as gradually reducing overall sweetness preference by decreasing exposure to intensely sweet foods and beverages. For individuals with specific clinical conditions, integrating these discussions into broader nutrition therapy—and, when indicated, consulting with a qualified diet-care professional—can help align dietary changes with long-term goals for health and well-being.

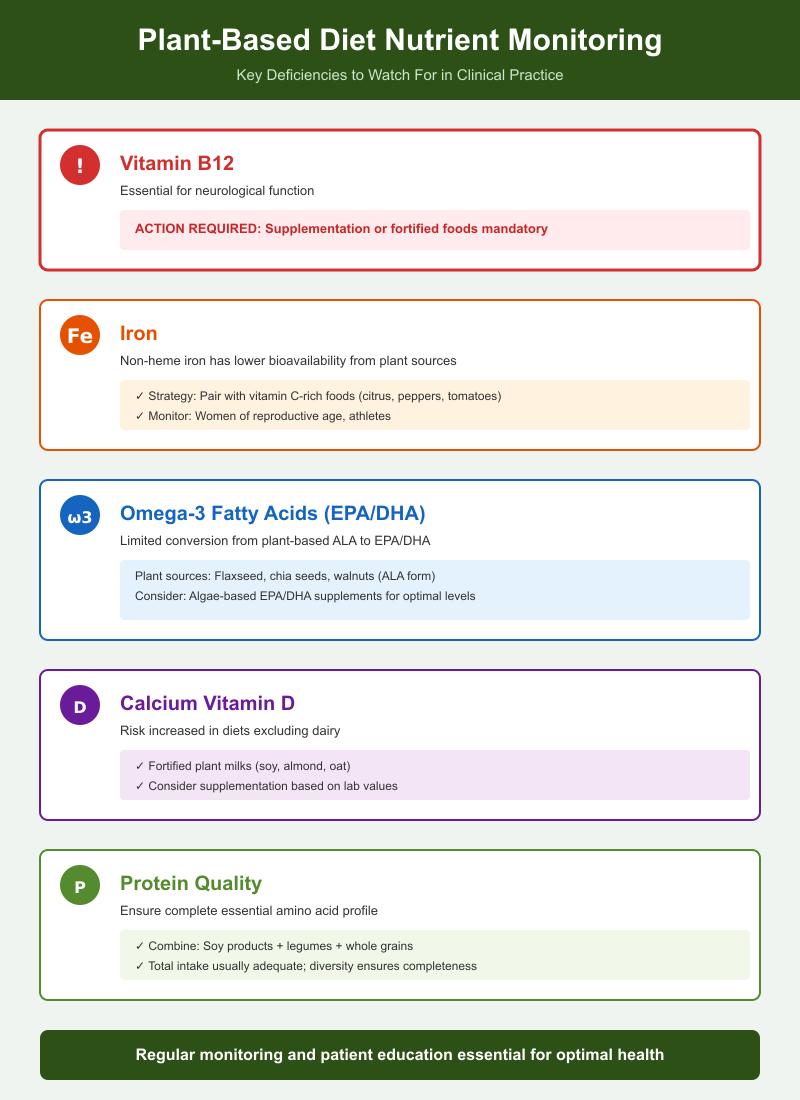

Can plant-based diets prevent disease or create nutritional gaps?

Plant-based diets, which emphasize vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds, have been associated with health-promoting effects in several chronic conditions. Evidence suggests that such dietary patterns can lower risk factors for obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes, primarily due to high fiber content, phytonutrients, and lower levels of saturated fat. Randomized controlled trials indicate that shifting to a plant-centered eating pattern can improve lipid profiles, reduce blood pressure, and support weight management.

However, poorly planned plant-based diets may create nutritional gaps. Nutrients like vitamin B12, iron, zinc, calcium, iodine, and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids may be insufficient if animal products and fortified foods are minimized. This emphasizes the importance of dietary planning to maintain overall health and prevent deficiencies.

Do plant-based nutrition and whole food plant-based approaches reduce obesity and cardiovascular disease?

Whole food plant-based approaches focus on minimally processed plant foods rather than refined or processed plant products. These diets are associated with reduced body weight, lower LDL-cholesterol, and improved cardiovascular health. Cohort studies and systematic reviews and meta-analyses show that individuals adhering to whole food plant-based patterns have lower incidence of heart disease, decreased blood pressure, and improved glycemic control compared with omnivorous or highly processed diets.

For example, a randomized controlled trial replacing typical Western dietary patterns with a whole food plant-based diet demonstrated significant reductions in body weight and improvements in blood lipid profiles over 16 weeks, highlighting the cardioprotective effects of such approaches.

What nutrient deficiencies or risks should health professionals watch for in plant-based diets?

Health professionals should be alert to the potential for deficiencies in:

- Vitamin B12: Essential for neurological function; supplementation or fortified foods are required.

- Iron: Non-heme iron from plant sources has lower bioavailability; pairing with vitamin C-rich foods can improve absorption.

- Omega-3 fatty acids: Conversion of ALA (from flaxseed, chia, walnuts) to EPA/DHA is limited.

- Calcium and Vitamin D: Especially in diets excluding dairy, fortified plant milks may be needed.

- Protein quality: While overall protein intake can be adequate, combining soy products, legumes, and grains ensures all essential amino acids are consumed.

Addressing these nutrients is critical to prevent unintended health consequences while maintaining the benefits of plant-based eating.

How does plant-based nutrition affect type 2 diabetes and metabolic health?

Plant-based diets improve metabolic outcomes through multiple mechanisms:

- High fiber content slows glucose absorption, improving post-prandial glycemia.

- Low saturated fat intake enhances insulin sensitivity and reduces risk of heart disease associated with diabetes.

- Diets rich in legumes, whole grains, and minimally processed plant foods improve weight management, supporting glycemic control and reducing type 2 diabetes risk.

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that plant-based diets significantly reduce HbA1c levels and fasting blood glucose in individuals with type 2 diabetes compared to conventional diabetic diets. Additionally, these diets positively affect metabolic risk factors, including blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol, and inflammation markers.

Are plant-based meats a healthy alternative or a processed food concern?

Plant-based meats, often marketed as alternatives to animal protein, are designed to mimic the taste, texture, and appearance of traditional meat while providing lower levels of saturated fat and zero cholesterol. They are frequently fortified with vitamins and minerals, such as B12 and iron, to approximate nutrient profiles of meat.

While these products may support reduced intake of saturated fat and contribute to a cardioprotective diet when replacing red or processed meats, they are inherently processed foods. Processing often involves texturizing plant proteins, adding flavoring agents, sodium, and other additives to enhance palatability. High sodium content and additives raise concerns about long-term health implications, particularly for cardiovascular health and metabolic regulation. Thus, while they offer an alternative to animal meat, they should not be viewed as nutritionally equivalent to whole food plant-based options.

How do plant-based meats compare to whole food plant-based options in terms of nutrition?

Whole food plant-based foods—such as legumes, beans, tofu, nuts, and whole grains—provide fiber, phytonutrients, and minimally processed protein, which collectively contribute to reduced risk factors for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease. In contrast, plant-based meats, despite having similar protein content, often lack fiber, and may contain refined oils and stabilizers.

For example, a serving of lentils provides not only protein but also soluble fiber that supports glycemic control and lowers LDL-cholesterol, whereas a plant-based burger patty may deliver protein and fortified micronutrients but minimal fiber and higher sodium. The overall health impact is therefore influenced not only by the protein content but also by the matrix of nutrients and bioactive compounds present in minimally processed plant foods.

Do plant-based meats affect body weight, metabolic risk factors, or cardiovascular health?

Evidence on long-term effects of plant-based meats is emerging but remains limited. Short-term studies suggest that replacing red meat with plant-based alternatives can modestly reduce body weight and lower saturated fat intake, potentially improving serum lipid profiles. However, because these products are processed and sometimes energy-dense, habitual consumption without balancing total caloric intake may limit weight loss or metabolic improvements.

A randomized controlled study comparing diets substituting traditional meat with plant-based meat found improvements in LDL-cholesterol and modest reductions in body weight over 8 weeks, indicating potential cardiovascular benefit. Nevertheless, health professionals emphasize that these benefits are greater when plant-based meats are part of an overall whole food plant-based nutrition approach rather than as standalone replacements within a diet high in processed foods.

Practical example: A diet that includes occasional plant-based burgers alongside abundant legumes, vegetables, and whole grains may support metabolic health, whereas a diet heavily reliant on highly processed plant-based meat products with refined carbohydrates may not confer the same benefits.

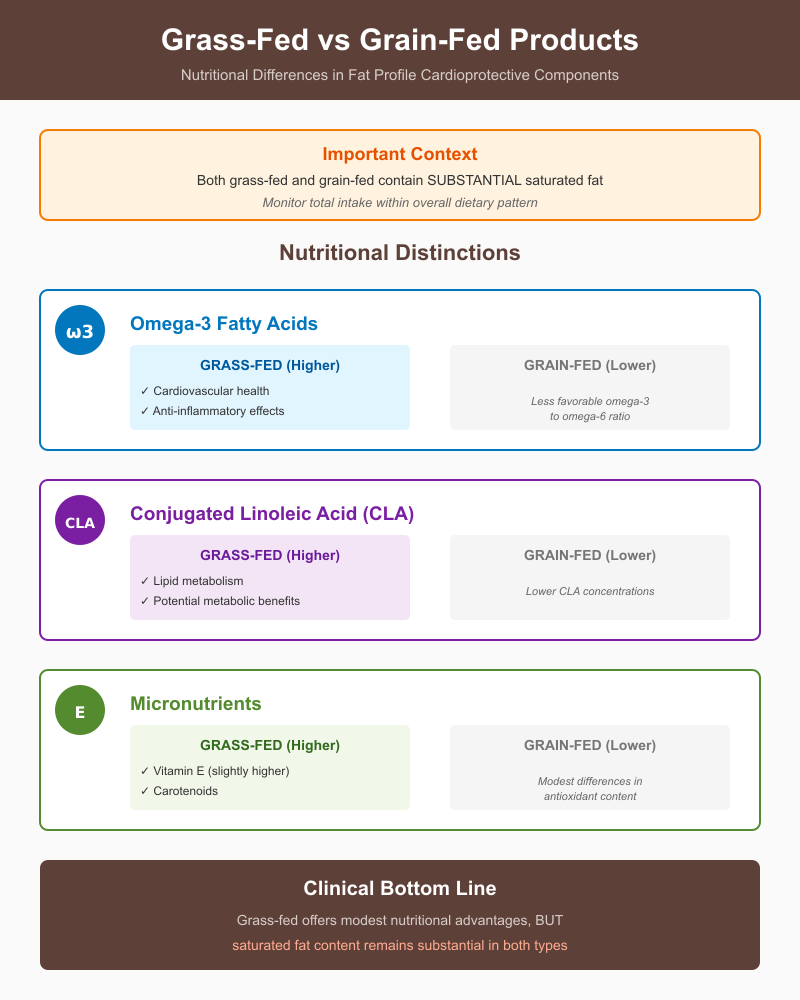

Does grain-fed vs grass-fed animal production matter for foods and nutrition?

The type of feed used in livestock production—grain-fed versus grass-fed—affects the nutrition profile of animal-derived foods. Grain-fed animals, commonly raised on corn or soy-based diets, tend to gain weight faster and produce meat with higher overall fat content. Grass-fed animals, which consume primarily pasture, often produce meat and dairy products with slightly lower total fat and a different distribution of fatty acids. These differences are not only relevant for saturated fat intake but also for bioactive compounds that may impact cardiovascular health.

For example, beef from grass-fed cattle generally contains higher concentrations of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and omega-3 fatty acids, which have been associated with cardioprotective effects in some nutrition studies. Grain-fed beef, while still a source of high-quality protein, typically has a higher omega-6 to omega-3 ratio, which may influence inflammation and lipid metabolism. Similarly, grass-fed dairy tends to have elevated levels of vitamins A and E and antioxidants compared with conventional grain-fed milk.

Are there meaningful differences in fat profile, saturated fat, and cardioprotective components?

While grass-fed meats and dairy often contain more favorable fatty acid profiles, the differences in saturated fat content are modest. Both grass-fed and grain-fed meats contain substantial saturated fat, so absolute intake should be monitored within the context of overall dietary patterns. The primary nutritional distinctions lie in:

- Omega-3 fatty acids: Grass-fed products provide higher levels, supporting cardiovascular health and anti-inflammatory effects.

- CLA: Found in higher concentrations in grass-fed meats, associated with modest improvements in lipid metabolism and potential metabolic benefits.

- Micronutrients: Grass-fed animal products may contain slightly higher vitamin E and carotenoids, contributing to overall health.

Despite these differences, studies show that the magnitude of impact on long-term disease risk is relatively small compared to the effects of replacing saturated fat with plant-based sources, whole grains, and unsaturated fats.

How should nursing students weigh environmental and health trade-offs of grain-fed versus grass-fed?

Evaluating grain-fed versus grass-fed systems requires considering both health consequences and sustainability:

- Health considerations: Grass-fed products offer minor nutritional advantages in terms of fatty acid composition and antioxidant content, but total saturated fat intake remains a critical factor. Selecting lean cuts and limiting portion sizes helps mitigate cardiovascular risk regardless of feed type.

- Environmental impact: Grass-fed livestock generally require more land and may produce higher methane emissions per unit of meat compared with grain-fed systems, raising questions about ecological sustainability. Conversely, pasture-based systems can support soil health and biodiversity.

Decision-making involves balancing these factors. Incorporating a variety of protein sources—including plant-based options, minimally processed foods and drinks, and moderate animal products—can optimize both long-term health and environmental outcomes. Emphasizing dietary patterns over single food choices ensures that the nutrition approach remains holistic, targeting body weight, metabolic risk factors, and cardiovascular health while respecting sustainability considerations.

Example: A diet combining small amounts of grass-fed meat, whole grains, legumes, and vegetables provides essential nutrients, improves the omega-3 to omega-6 balance, and supports heart health, even if absolute differences between grass-fed and grain-fed meats are moderate.

Which dietary patterns best support weight, diabetes control, and overall health?

Evidence from nutrition studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials suggests that several dietary patterns can improve body weight, glycemic control, and long-term health outcomes. Notable approaches include the Mediterranean diet, low-carbohydrate diets, and principles of intuitive eating, each offering distinct mechanisms and benefits. Common characteristics that support weight management and type 2 diabetes control include:

- Emphasis on whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and seeds.

- Moderate protein intake from plant or lean animal sources.

- Limited consumption of highly processed foods, added sugars, and refined carbohydrates.

- Attention to dietary variety and nutrient adequacy to prevent deficiencies.

These evidence-based nutrition topics form the foundation of health-promoting dietary patterns that reduce risk factors for obesity, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic dysfunction.

How do low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, and intuitive eating approaches compare for type 2 diabetes?

- Low-carbohydrate diets:

Low-carbohydrate patterns reduce post-prandial glucose spikes and improve glycemic control by limiting carbohydrate intake and promoting the use of fat for energy. Several meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials report significant reductions in HbA1c and body weight in individuals with type 2 diabetes following low-carbohydrate interventions. However, overly restrictive carbohydrate approaches may challenge long-term adherence and nutrient adequacy, highlighting the importance of monitoring foods and drinks to maintain overall health. - Mediterranean diet:

Characterized by high consumption of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, olive oil, nuts, moderate fish, and limited red meat, this dietary pattern is rich in cardioprotective fats and fiber. Research demonstrates reductions in body weight, improved insulin sensitivity, and decreased risk of heart disease. The Mediterranean diet also supports metabolic health through a high intake of minimally processed, nutrient-dense foods that improve health outcomes beyond glycemic control. - Intuitive eating:

This approach emphasizes responsiveness to internal hunger and satiety cues rather than rigid food restriction. Studies indicate that intuitive eating can support healthy relationship with food, reduce disordered eating behaviors, and improve psychological well-being. While its impact on glycemic control may be indirect, combining intuitive eating with attention to carbohydrate quality and whole grain intake can contribute to sustainable weight management and long-term health.

What is the role of whole grain, carbohydrate quality, and minimally processed foods in obesity and metabolic health?

The quality of carbohydrate intake significantly affects metabolic risk factors and body weight. Whole grains provide fiber, essential vitamins, and minerals that improve satiety, reduce post-prandial glucose excursions, and lower LDL-cholesterol. Minimally processed foods—such as oats, quinoa, brown rice, legumes, fruits, and vegetables—promote slower digestion, better glycemic control, and reduced inflammation compared with refined grains and highly processed carbohydrates. High-quality carbohydrate sources also positively influence microbiome composition, further supporting overall health and metabolic resilience.

Example: Replacing white bread with whole grain bread and pairing with legumes or vegetables in a meal can attenuate glucose spikes, improve satiety, and contribute to obesity prevention and type 2 diabetes management.

How can health professionals balance food restriction concerns, relationship with food, and health at every size principles?

Modern nutrition guidance recognizes that strict dietary restriction can negatively affect psychological well-being and foster disordered eating patterns. The health at every size approach prioritizes metabolic health, physical activity, and nutrient adequacy rather than focusing solely on weight.

- Emphasize eating patterns over individual nutrient elimination, encouraging healthy eating habits that are sustainable and enjoyable.

- Support positive relationship with food by promoting mindful eating, flexibility, and avoidance of guilt or moral judgments tied to food choices.

- Integrate evidence-based recommendations for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular health with patient-centered strategies that respect preferences, culture, and lifestyle.

Example: A patient can follow a Mediterranean-style or low-carbohydrate approach for glycemic management while practicing intuitive eating principles, focusing on nutrient-dense foods like whole grains, vegetables, and legumes, without imposing strict caloric limits that could undermine adherence or psychological well-being.

Conclusion

Nutrition remains one of the most dynamic and debated areas of healthcare, with evolving evidence continually challenging established guidelines. From the controversies surrounding saturated fat and cardiovascular health, to debates over artificial sweeteners, plant-based diets, and plant-based meats, it is clear that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to dietary recommendations. Each nutrition topic carries nuanced implications for metabolic health, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and long-term cardiovascular outcomes, highlighting the importance of considering the whole diet rather than isolated nutrients.

Whole, minimally processed foods, balanced macronutrient intake, and careful attention to nutrient adequacy consistently emerge as foundational elements of health-promoting eating patterns. At the same time, understanding the potential benefits and limitations of processed alternatives, sweeteners, and novel dietary trends allows for informed decision-making that is evidence-based and personalized.

These trending nutrition controversies underscore the need for critical appraisal of nutrition studies, careful evaluation of health outcomes, and application of nutrition knowledge in practical settings. Ultimately, the goal is to integrate scientific evidence with individual needs and preferences, fostering dietary strategies that optimize overall health, mitigate disease risk, and support sustainable, healthy eating practices across populations.

In a field where new research continuously reshapes understanding, maintaining an open, analytical, and evidence-informed perspective ensures that dietary guidance remains both credible and practical, bridging the gap between controversy and actionable health advice.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the controversial topics regarding nutrition?

Controversial nutrition topics include debates over saturated fat and heart disease, the safety and metabolic effects of artificial sweeteners, the health impacts of plant-based diets versus animal products, the role of low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diets, and concerns over processed foods and additives. Other hot topics include sugar consumption, dietary guidelines, and conflicting evidence on weight management approaches.

What are some good food debates?

Popular food debates focus on:

- Meat vs. plant-based diets for health and sustainability.

- Low-fat vs. low-carb diets for weight loss and type 2 diabetes control.

- The use of artificial sweeteners versus sugar.

- Organic vs. conventionally produced foods.

- The health impact of processed vs. whole foods.

What is the most prominent nutrition issue in the world?

The global prevalence of obesity and related chronic diseases—including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome—is the most pressing nutrition issue. This is fueled by rising consumption of processed foods, high sugar and saturated fat intake, and shifts in eating patterns worldwide.

Why is nutrition so controversial?

Nutrition is controversial because scientific research often produces conflicting results, dietary impacts vary among individuals, and the food industry, media, and cultural norms influence public perceptions. Additionally, evolving evidence, methodological differences in nutrition studies, and the complex interactions between diet, genetics, and lifestyle contribute to ongoing debates and differing expert opinions.