How to Create a Critically Appraised Topic to Critically Appraise Evidence for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice

In modern healthcare, the integration of evidence-based practice (EBP) into clinical decision-making is essential for improving patient care and ensuring optimal outcomes. Central to this process is the critically appraised topic, a structured tool that enables clinicians to systematically evaluate research evidence and translate it into practical guidance for patient care. Far from being a purely academic exercise, a critically appraised topic allows healthcare professionals—including nurses, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists—to organize, assess, and summarize the best available evidence around a specific clinical question.

The process of critically appraising research involves more than simply reading studies; it requires a careful assessment of methodological quality, study design, and the applicability of findings to a given clinical context. By focusing on a well-defined clinical question, clinicians can determine which studies provide the most relevant and reliable evidence, whether through randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, or qualitative research. Critically appraised topics also serve as a bridge between large-scale systematic reviews or meta-analyses and day-to-day clinical decision-making, offering concise, actionable summaries of research that can inform treatment strategies and patient care.

For nursing students and early-career clinicians, understanding how to create and use a critically appraised topic is an essential skill in evidence-based clinical practice. It cultivates critical appraisal skills, promotes a structured approach to evaluating scientific literature, and enhances the ability to make informed clinical decisions. This article provides a comprehensive guide to developing a critically appraised topic—from formulating a focused PICO question and designing an effective search strategy to appraising the methodological quality of studies and summarizing findings for clinical use. Through this structured approach, healthcare professionals can navigate the vast landscape of research evidence with confidence, ensuring that patient care is guided by rigorously evaluated and clinically relevant information.

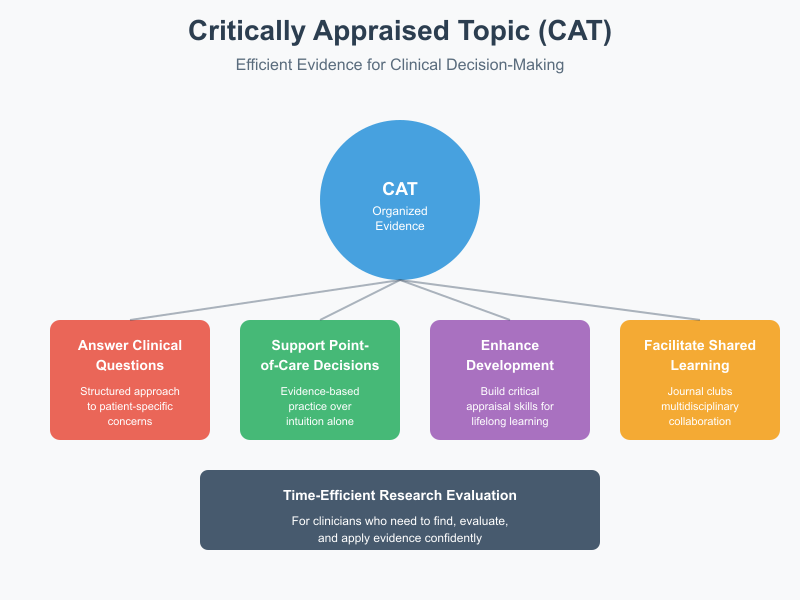

What is a critically appraised topic and how does it fit into evidence-based practice (ebp)?

A critically appraised topic is a structured summary of research findings that directly addresses a clinical question encountered in everyday care. Unlike broad literature reviews, this concise tool focuses on the most relevant studies and evaluates them systematically to inform evidence‑based decisions. Essentially, it distills clinical evidence into a format that clinicians can use quickly, helping bridge the gap between research and practice.

In evidence‑based practice, clinical decision‑making is grounded in the best available evidence, clinical expertise, and patient preferences. A critically appraised topic supports this process by providing a clear, evidence‑oriented answer to questions that arise at the bedside, in community settings, or during journal clubs. For example, a nurse may encounter a question about the effectiveness of early mobilization in preventing postoperative complications. By creating a critically appraised topic, that nurse searches for relevant randomized controlled trials and cohort studies, evaluates their methodological quality, and summarizes findings to guide practice.

What is a critically appraised topic and its purpose in clinical practice?

In clinical environments where time is limited, clinicians need efficient ways to find, evaluate, and apply research. A critically appraised topic is designed precisely for this — it organizes relevant evidence to help practitioners act confidently and safely.

Purpose in Clinical Practice

- Answering Specific Clinical Questions:

When a clinician encounters a focused patient concern — such as whether a particular wound care intervention reduces infection rates — a critically appraised topic provides a structured approach to answering that question. It highlights which research studies are relevant, what outcomes were measured, and what conclusions can be drawn. - Supporting Point‑of‑Care Decisions:

For instance, if a patient with chronic pain asks about the effectiveness of therapeutic ultrasound, the clinician can use a critically appraised topic summarizing pertinent research rather than relying on memory or intuition alone. This aligns with evidence‑based practice and reduces variability in patient care. - Enhancing Professional Development:

For students and practicing clinicians alike, engaging in the critical appraisal process develops critical appraisal skills. These skills — such as assessing selection bias or interpreting peer‑review findings — strengthen lifelong learning and support high‑quality care delivery. - Facilitating Shared Learning:

Critically appraised topics are often used in journal club sessions where multidisciplinary teams discuss evidence together, promoting collaboration between nursing, occupational therapy, or physiotherapy professionals.

How does a critically appraised topic relate to evidence based medicine and best available evidence?

Evidence‑based medicine (EBM) focuses on integrating clinical expertise with research findings and patient values. Within this paradigm, clinicians seek the level of evidence that is most likely to reflect truth and minimize bias. A critically appraised topic directly supports this by:

- Identifying High‑Quality Studies: It prioritizes designs such as randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews. These designs are generally considered higher in the evidence hierarchy because they use rigorous methods to reduce bias.

- Evaluating Methodological Quality: The clinician assesses each study’s methodological strengths and limitations, identifying factors that might affect the reliability of results — for example, whether a clinical trial used random allocation or adequate blinding.

- Synthesizing Evidence Clearly: A summary critically appraised topic not only lists findings but interprets them in context, helping clinicians discern best evidence for practice decisions.

For example, suppose multiple studies examine the effectiveness of different splinting techniques for wrist fractures. A critically appraised topic will organize research findings, compare outcomes, and determine which technique appears most effective based on current evidence. This structured summary serves as a practical tool for clinicians integrating research into patient care.

When should clinicians use a critically appraised topic versus a systematic review or meta-analysis?

While all three — critically appraised topics, systematic reviews, and meta‑analyses — summarize evidence, they differ in scope, depth, and purpose.

Critically Appraised Topic

Use a critically appraised topic when:

- A specific or narrow clinical question emerges in day‑to‑day practice.

- Time is limited and a quick yet evidence‑grounded answer is needed.

- The goal is to translate evidence into an immediate clinical decision.

Example: A nurse wants to know whether early ambulation reduces pulmonary complications in elderly postoperative patients. Rather than waiting for or conducting a comprehensive review, a critically appraised topic offers a focused answer based on the most pertinent studies.

Systematic Review

Use a systematic review when:

- The question is broad and requires comprehensive coverage of all relevant research.

- You need to reduce bias through exhaustive searching and transparent methods.

- Practice guidelines or policy documents are being developed.

Meta‑Analysis is part of some systematic reviews where results from multiple quantitative studies are statistically combined, increasing power and precision.

Example: A systematic review of interventions to prevent pressure injuries gathers all randomized and cohort studies across years of research to establish generalizable recommendations.

How do I formulate a clinical question and PICO for a critically appraised topic?

Formulating a clinical question is the first and most crucial step when creating a critically appraised topic. A clearly defined question helps ensure that the search for relevant evidence is focused, efficient, and applicable to clinical practice. Without a precise question, clinicians risk retrieving an overwhelming amount of literature, including studies that are irrelevant or methodologically weak.

Example: A nurse wants to know whether early mobilization improves recovery after abdominal surgery. Without structuring this into a clear question, searches might return studies about exercise in unrelated patient populations, wasting time and resources. Formulating the question systematically ensures that the subsequent appraisal process evaluates best available evidence efficiently.

How do I write a focused question using pico format for a clinical question?

The PICO format is a cornerstone of evidence-based practice that helps transform broad clinical concerns into answerable questions suitable for critical appraisal. PICO stands for:

- P (Population or Patient Problem): Define the group of patients or clinical condition.

- I (Intervention): Specify the treatment, procedure, or approach being considered.

- C (Comparison): Identify the alternative intervention, placebo, or standard care for comparison.

- O (Outcome): Determine the clinical outcome of interest.

Example: Suppose a nurse wants to evaluate whether incentive spirometry prevents postoperative pulmonary complications:

- P: Adult patients undergoing abdominal surgery

- I: Incentive spirometry

- C: Standard postoperative care without spirometry

- O: Reduction in pulmonary complications

This PICO question—“In adult patients undergoing abdominal surgery, does incentive spirometry compared to standard care reduce postoperative pulmonary complications?”—is focused and facilitates a search for studies that are directly applicable to practice. The PICO approach also helps define the study design likely to provide robust evidence, such as randomized controlled trials or systematic reviews.

Which search terms and search strategy best capture relevant studies for the question?

After formulating a PICO question, clinicians must develop an effective search strategy to capture relevant studies for appraisal.

Step 1: Extract Keywords from PICO

Each PICO element generates potential search terms:

- P (Population): “adult patients,” “postoperative patients”

- I (Intervention): “incentive spirometry,” “deep breathing exercises”

- C (Comparison): “standard care”

- O (Outcome): “pulmonary complications,” “lung function”

Step 2: Use Boolean Operators

Combine search terms using AND to narrow results (e.g., postoperative AND incentive spirometry AND pulmonary complications) and OR to capture synonyms (e.g., deep breathing OR incentive spirometry). This ensures retrieval of all relevant evidence.

Step 3: Database Controlled Vocabulary

Databases like PubMed utilize controlled vocabulary (MeSH terms) that index articles under standardized headings. Using MeSH ensures that your search includes studies even if authors used different terminology.

Step 4: Refine and Filter

Apply filters such as language, publication date, or type of study (e.g., systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials) to focus on the best available evidence.

Example: A search for the above PICO question in PubMed might combine MeSH terms and keywords:

(“Abdominal Surgery”[MeSH] OR “Postoperative Patients”) AND (“Incentive Spirometry”[MeSH] OR “Deep Breathing Exercises”) AND (“Pulmonary Complications”[MeSH] OR “Lung Function”)

This strategy balances sensitivity (finding all relevant studies) with specificity (excluding irrelevant studies), a key principle in evidence-based practice.

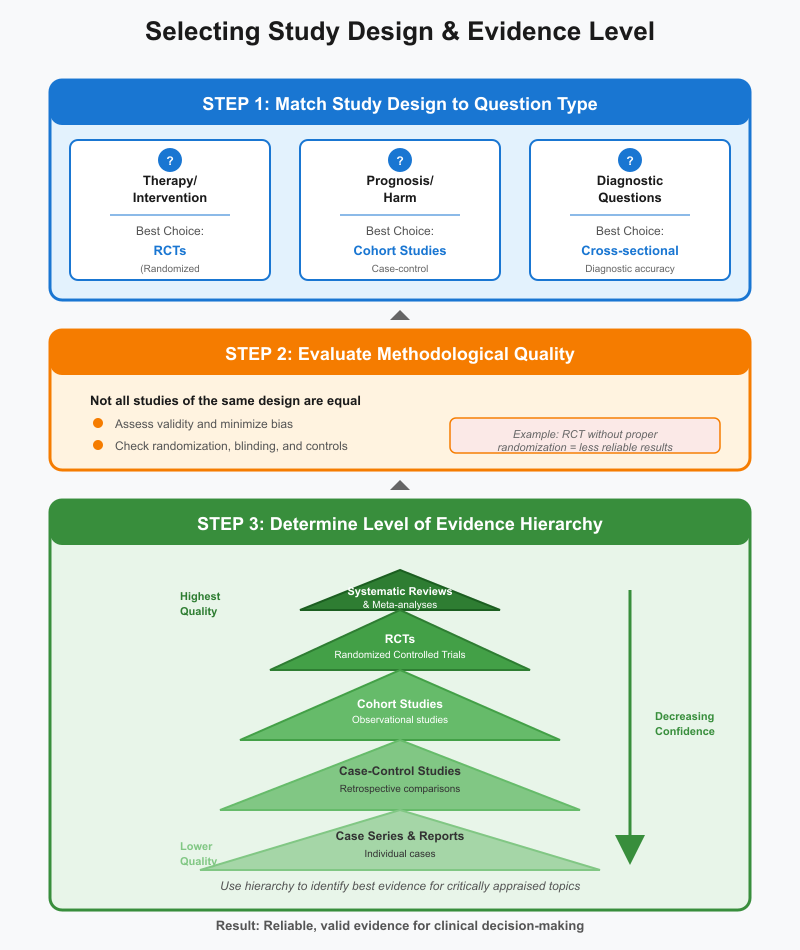

How can clinicians around a clinical question choose study design and level of evidence?

After retrieving studies, clinicians must select those that provide the most reliable answers. The study design and level of evidence are critical in determining how much confidence can be placed in the findings.

Step 1: Match Study Design to Question Type

- Therapy/intervention questions: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are preferred.

- Prognosis or harm questions: Cohort studies or case-control studies may be more appropriate.

- Diagnostic questions: Cross-sectional or diagnostic accuracy studies are suitable.

Step 2: Evaluate Methodological Quality

Not all studies of the same design are equal. Assessing methodological quality ensures that the evidence is valid, minimizing bias and errors. For example, an RCT that lacks randomization or blinding may provide less reliable results.

Step 3: Determine Level of Evidence

Hierarchy charts help rank evidence, typically placing systematic reviews and meta-analyses at the top, followed by RCTs, cohort studies, and case series. This helps clinicians identify best evidence for their critically appraised topic.

Example: Returning to the incentive spirometry question, a systematic review of RCTs evaluating postoperative pulmonary outcomes provides stronger evidence than a single cohort study or expert opinion. A critically appraised topic would summarize this evidence, appraise its quality, and make it actionable for nursing practice.

What search methods identify available evidence, reviews and critically appraised resources?

When should I include rapid review, meta-analysis, practice guidelines or qualitative research?

The type of evidence included in a critically appraised topic depends on the clinical question, the urgency of the situation, and the depth of information required. Understanding when to include each type of research ensures that evidence-based practice (EBP) is both efficient and clinically relevant.

- Rapid Reviews:

Rapid reviews are condensed forms of systematic reviews that synthesize evidence quickly, often to inform urgent clinical decisions. They are particularly useful in situations where time constraints make it impractical to conduct a full systematic review. While rapid reviews may not be as comprehensive, they provide timely guidance based on available evidence.

Example: During an outbreak of hospital-acquired infections, a nurse manager may rely on a rapid review to determine which antiseptic protocols have the strongest evidence for reducing infection rates. - Meta-Analyses:

A meta-analysis statistically combines results from multiple studies, usually randomized controlled trials (RCTs), to provide more precise estimates of treatment effects. Include meta-analyses when multiple studies address the same intervention and outcome. They are particularly valuable for identifying best evidence and reducing uncertainty in clinical decision-making.

Example: For evaluating the effectiveness of compression therapy in preventing venous leg ulcers, a meta-analysis of several RCTs provides stronger guidance than any single study. - Practice Guidelines:

Practice guidelines summarize evidence and provide recommendations for patient care based on systematic evaluation of the literature. They are most useful when developing clinical protocols or standardizing care across settings. Guidelines often combine systematic reviews, expert consensus, and clinical experience.

Example: The British Journal of Dermatology publishes guidelines on managing chronic wounds, which nurses and clinicians use to align care with the best available evidence. - Qualitative Research:

While much of EBP emphasizes quantitative outcomes, qualitative research provides insights into patient perspectives, experiences, and barriers to care. This type of research is valuable when understanding context-specific factors that influence the success of an intervention.

Example: In physiotherapy, qualitative studies may explore patient adherence to home exercise programs, informing nurses and therapists about practical strategies to improve engagement.

Summary: Each type of evidence has a unique purpose: rapid reviews for urgency, meta-analyses for statistical precision, practice guidelines for standardized care, and qualitative research for patient-centered insights. Selecting the appropriate type depends on the clinical question, the level of certainty required, and the context of care.

What are practical tips for search strategy and selecting relevant studies for a summary?

An effective search strategy ensures that your critically appraised topic captures relevant evidence efficiently, minimizing bias while maximizing applicability. The following tips are essential:

- Develop a Structured Search Plan:

Begin with a clear PICO question. Identify keywords and MeSH terms for each PICO element. Decide in advance which type of study or level of evidence is most appropriate for your clinical question. - Use Boolean Operators:

Combine search terms using AND to narrow results (ensuring all concepts appear) or OR to include synonyms and broaden results. This balances sensitivity (capturing all relevant studies) and specificity (excluding irrelevant ones).

Example: “Postoperative care AND early mobilization AND pulmonary complications” ensures all studies address the same concepts. - Select Appropriate Databases and Filters:

Use databases like PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library. Apply filters for study design (e.g., RCTs, systematic reviews), publication date, and language. This focuses your search on high-quality research evidence. - Screen Studies Efficiently:

Review titles and abstracts to assess clinical relevance and methodological quality. Exclude studies that do not directly answer your clinical question or that have significant limitations (e.g., small sample size, selection bias). - Document Your Search:

Keep a detailed record of databases, search terms, filters, and the number of articles retrieved. This ensures transparency and reproducibility, which is essential when sharing your critically appraised topic in journal clubs or professional settings. - Prioritize Evidence Based on Clinical Relevance:

Focus on studies that answer the specific question and are applicable to your patient population. High-level evidence such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses should be prioritized, followed by RCTs, cohort studies, and qualitative research when appropriate. - Iterative Searching:

Refine your strategy based on initial results. Sometimes additional synonyms, narrower population definitions, or expanded outcome measures improve relevance and quality of included studies.

Example: A nursing student preparing a critically appraised topic on pressure ulcer prevention might start with a systematic search for RCTs in PubMed, then add practice guidelines from CEBM, and finally include qualitative studies exploring patient adherence to pressure relief protocols. The summary integrates all this evidence to inform bedside care.

How do I appraise the methodological quality and level of evidence of studies?

Appraising the methodological quality of studies is a cornerstone of developing a critically appraised topic. It ensures that the research evidence being used is reliable, valid, and applicable to clinical practice. Methodological quality refers to how rigorously a study is designed, conducted, and reported, including the appropriateness of its study design, sample size, and measurement methods.

Appraising methodological quality typically involves asking:

- Was the study design appropriate for the clinical question?

- Were participants representative of the population of interest?

- Were outcomes measured reliably and consistently?

- Was the study conducted to minimize bias?

Example: Consider evaluating studies on the effectiveness of early mobilization in ICU patients. A well-designed randomized controlled trial with adequate randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding would be considered methodologically strong, while a small, non-randomized cohort study may be weaker.

Once the methodological quality is appraised, studies are assigned a level of evidence, which indicates the confidence clinicians can have in the results. High-quality RCTs or systematic reviews of RCTs are usually rated higher than observational studies or case series.

What critical appraisal skills help evaluate randomized controlled trials and cohort studies?

Critical appraisal skills are essential for interpreting research and translating it into evidence-based practice. Key skills include:

- Understanding Study Design:

- Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs): Assess randomization, allocation concealment, blinding, follow-up rates, and intention-to-treat analysis.

- Cohort Studies: Evaluate how cohorts were selected, whether exposure was clearly defined, how outcomes were measured, and the duration of follow-up.

- Assessing Internal Validity:

Identify biases that could distort study results. This includes selection bias, performance bias, and detection bias. - Analyzing Outcome Measures:

Evaluate whether the outcomes are clinically relevant, valid, and measured consistently across participants. - Interpreting Results:

Assess whether the statistical analysis is appropriate, confidence intervals are provided, and whether results are generalizable to your patient population.

Example: A nurse critically appraising an RCT on wound care interventions should check whether participants were randomly assigned, whether the staff providing care were blinded to the intervention, and whether the reported reduction in infection rates is statistically and clinically meaningful.

How do I assess risk of bias, study design, and methodological limitations?

Risk of bias refers to factors in the study design or conduct that could systematically affect the results. Common areas to evaluate include:

- Selection Bias:

Occurs if the study population is not representative or if randomization is inadequate. - Performance Bias:

Differences in care provided apart from the intervention can influence outcomes. - Detection Bias:

Bias introduced if outcome assessment is influenced by knowledge of intervention assignment. - Attrition Bias:

Loss of participants during follow-up may distort study outcomes. - Reporting Bias:

Occurs when only favorable results are published or emphasized.

Methodological limitations also include small sample size, short follow-up periods, or unstandardized outcome measures. Assessing these limitations ensures that clinicians understand the strength and applicability of clinical evidence.

Example: In a cohort study on physiotherapy for stroke patients, a high risk of bias might exist if patients self-selected into intervention groups, follow-up was inconsistent, or outcomes were not measured using standardized tools.

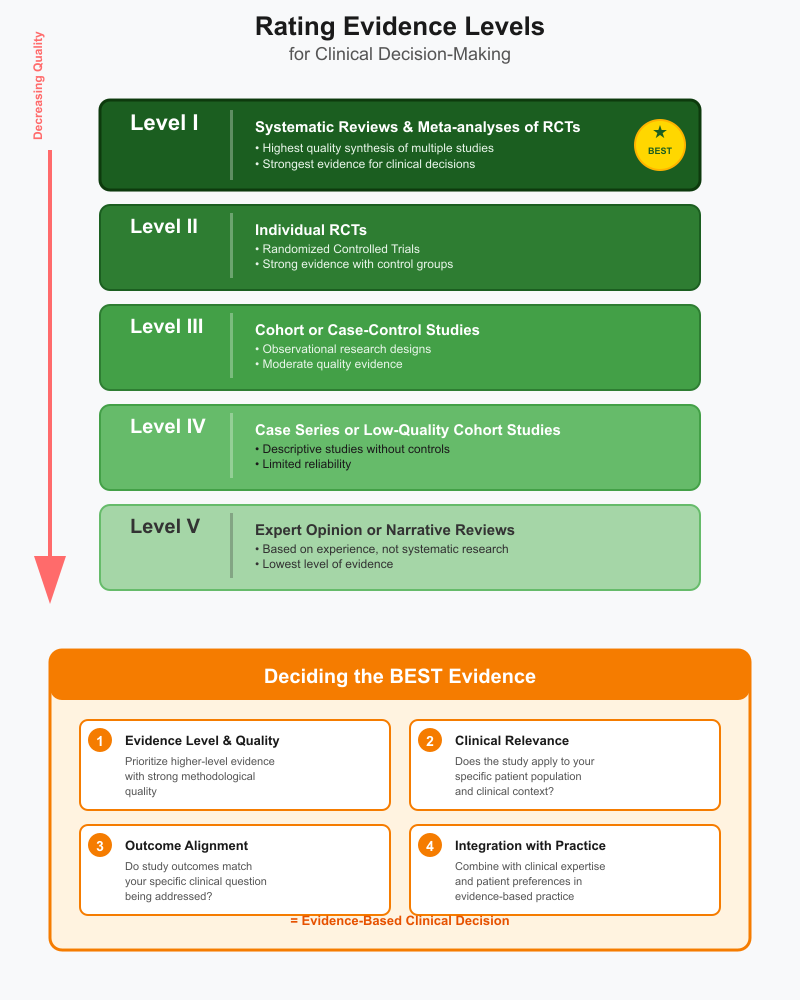

How do I rate level of evidence and decide what is the best evidence for clinical decision?

Rating the level of evidence allows clinicians to determine which studies should carry more weight in clinical decision-making. Commonly used hierarchies include:

- Level I: Systematic reviews or meta-analyses of RCTs

- Level II: Individual RCTs

- Level III: Cohort or case-control studies

- Level IV: Case series or low-quality cohort studies

- Level V: Expert opinion or narrative reviews

To decide what constitutes the best evidence:

- Prioritize higher-level evidence with strong methodological quality.

- Consider the clinical relevance of the study to your patient population.

- Evaluate whether the study outcomes align with the specific clinical question being addressed.

- Integrate findings with clinical expertise and patient preferences as part of evidence-based practice.

Example: For a nurse deciding whether to implement a new pressure injury prevention protocol, a systematic review of RCTs (Level I) demonstrating reduced incidence would provide the best evidence. If no high-level evidence exists, well-designed cohort studies or practice guidelines may inform practice, with awareness of their limitations.

How do I write and use a summary or summary critically appraised topic in clinical practice?

A summary critically appraised topic (CAT) is a concise, structured synthesis of the best available evidence related to a specific clinical question. The primary purpose is to provide clinicians with a clear, actionable overview that can be applied directly at the point of care. Writing a CAT requires careful organization, critical appraisal of included studies, and clear articulation of clinical relevance.

Steps to Write a CAT Summary:

- State the Clinical Question Clearly: Use PICO or focused question format to define the problem.

- Describe Search Strategy: List databases, search terms, and filters used to identify relevant studies, including systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, or practice guidelines.

- Appraise Included Studies: Summarize methodological quality, risk of bias, study design, and level of evidence.

- Synthesize Findings: Provide a concise summary of outcomes and their relevance to practice. Highlight whether the intervention is supported by evidence-based practice and clinical evidence.

- State Implications for Practice: Explain how the findings can be applied to patient care or clinical decision-making.

Example: A physiotherapist may prepare a CAT on the effectiveness of constraint-induced movement therapy in stroke rehabilitation. The summary includes a PICO question, search methods using PubMed and PEDro, appraisal of RCTs and cohort studies, and a conclusion recommending its implementation based on best evidence.

In clinical practice, CAT summaries help clinicians access relevant evidence quickly, improving efficiency and reducing reliance on memory or outdated practices. They also promote critical appraisal skills among students and staff, facilitating ongoing learning and professional development.

What elements should a critically appraised topic summary include for clinicians and journal club use?

A high-quality CAT summary should include the following elements to maximize utility for clinical practice and journal club discussion:

- Title and Clinical Question: Clearly states the specific clinical question the CAT addresses.

- Background and Rationale: Explains the clinical relevance, highlighting gaps in current practice or uncertainties that prompted the appraisal.

- Search Strategy: Details the electronic resources used (e.g., PubMed, CINAHL), search terms, and study selection criteria.

- Included Studies: Lists all relevant studies with study design, sample size, and key outcomes.

- Critical Appraisal: Evaluates methodological quality, risk of bias, and level of evidence.

- Summary of Findings: Synthesizes results into clear recommendations for practice.

- Implications for Practice: Connects findings to clinical decision-making and highlights applicability to patient care.

- References: Full citations for all included studies, ensuring transparency and credibility.

Example: During a journal club, a nursing team presents a CAT on early mobilization in postoperative patients. The structured summary allows discussion of the study design, appraisal, and clinical relevance, promoting collaborative decision-making and understanding of evidence-based practice.

How can a critically appraised topic inform clinical decision making in physiotherapy, occupational therapy or veterinary medicine?

CATs are versatile tools for translating evidence-based practice into various clinical disciplines:

- Physiotherapy: CATs can summarize randomized controlled trials on exercise interventions, helping clinicians choose the most effective therapy for patient recovery.

Example: A CAT on aerobic exercise for chronic low back pain enables physiotherapists to implement evidence-supported protocols. - Occupational Therapy: CATs guide decision-making for interventions targeting functional independence or daily living activities.

Example: A CAT evaluating adaptive equipment for stroke patients helps occupational therapists recommend devices that improve patient care outcomes. - Veterinary Medicine: CATs support clinical decisions in animal health by summarizing systematic reviews, RCTs, and observational studies.

Example: A CAT on analgesic use in dogs post-surgery informs veterinarians of the most effective pain management strategies, ensuring evidence-based treatment.

In each field, CATs bridge the gap between scientific literature and practice, allowing clinicians to implement interventions supported by best evidence while considering feasibility, patient preferences, and resources.

How do I present findings to support evidence-based practice and ongoing appraisal?

Presenting CAT findings effectively ensures that clinical teams can use evidence to inform decisions and encourage continuous learning:

- Structured Presentation: Organize the summary according to CAT elements—clinical question, search strategy, appraisal, and conclusions. Use bullet points or tables for clarity.

- Visual Aids: Include summary tables, graphs, or charts to display study design, level of evidence, and outcomes. This enhances understanding in journal clubs or team meetings.

- Clinical Bottom Line: Highlight the key recommendation derived from the best available evidence. Emphasize practical implications for bedside care.

- Facilitate Discussion: Encourage questions about applicability, critical appraisal findings, and limitations of the evidence. This promotes ongoing appraisal and helps staff stay current with new research.

- Documentation and Accessibility: Store CATs in departmental databases, shared folders, or learning management systems to ensure that clinicians can reference them when making decisions or educating patients.

Example: A nursing unit presents a CAT on pressure ulcer prevention during a weekly journal club. A table summarizing included studies, methodological quality, and recommendations allows staff to adopt evidence-based interventions efficiently while discussing practical considerations for patient care.

Conclusion

A critically appraised topic serves as a vital bridge between research evidence and clinical practice, enabling nursing students and clinicians to make informed, patient-centered decisions. By systematically formulating a clinical question, utilizing the PICO framework, and conducting structured searches of available evidence, practitioners can efficiently identify best evidence to guide interventions. The process of critical appraisal—evaluating methodological quality, risk of bias, and level of evidence—ensures that recommendations are grounded in reliable and applicable research rather than anecdotal experience.

Moreover, developing and presenting a well-structured CAT summary enhances the translation of evidence into practice. Whether used in journal clubs, bedside decision-making, or interdisciplinary collaboration, CATs provide a concise, accessible synthesis of relevant studies, including randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, practice guidelines, and qualitative research. For disciplines such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or veterinary medicine, CATs support tailored, evidence-based interventions while fostering critical thinking and ongoing appraisal skills.

Ultimately, mastering the creation and use of critically appraised topics empowers nursing students and clinicians to uphold the principles of evidence-based practice, optimize patient outcomes, and maintain clinical excellence. CATs are not merely academic exercises—they are practical, actionable tools that ensure care decisions are scientifically sound, contextually appropriate, and continuously updated in alignment with evolving research findings.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to perform a critically appraised topic?

To perform a critically appraised topic (CAT), start by formulating a clear clinical question, usually using the PICO format. Conduct a structured search of available evidence in databases such as PubMed, CINAHL, or Cochrane Library. Select relevant studies including randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, or practice guidelines. Critically appraise the methodological quality, risk of bias, and level of evidence. Finally, summarize findings in a structured format, highlighting implications for evidence-based clinical practice.

What type of research is a critically appraised topic?

A CAT is not a primary research study but a synthesis of existing research. It typically incorporates randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and qualitative research, critically appraised to provide best available evidence for a specific clinical question.

What is critical appraisal in nursing research?

Critical appraisal is the systematic evaluation of research studies to determine their trustworthiness, relevance, and applicability to clinical practice. It involves assessing study design, methodological quality, risk of bias, and level of evidence to decide whether the findings can inform evidence-based practice.

How do you write a critical appraisal?

Writing a critical appraisal involves summarizing a study’s purpose, design, population, intervention, and outcomes. Evaluate the methodological quality, including sample selection, data collection, and risk of bias. Discuss the level of evidence, strengths, limitations, and implications for clinical practice. Conclude with a recommendation about the applicability of the findings to patient care or nursing interventions.